Chimpanzee

Genetic similarity between humans and chimpanzees = between 96% and 99.4%

‘If you took two Plasticene amoebae and turned one into a chimpanzee, the other into a human being, almost all the changes you would make would be the same. Both would need hair, dry skin, a spinal column and three little bones in the middle ear…There is no bone in the chimpanzee body that I do not share. There is no known chemical in the chimpanzee brain that cannot be found in the human brain. There is no known part of the immune system, the digestive system, the vascular system, the lymph system or the nervous system that we have and chimpanzees do not, or vice versa. There is not even a brain lobe in the chimpanzee brain that we do not share.’ Matt Ridley, Genome: The Autobiography of a Species in 23 Chapters, Fourth Estate, 2000

“Everybody sort of wonders what makes us human.” Kerstin Lindblad-Toh, Co-Director, Genome Sequence and Analysis Program, Massachusetts Institute of Technology Center for Genome Research, US

‘Nor was the close relation of the human to other primates altogether ignored: Lord Monboddo insisted (to much mockery) that the orang-utan, though mute, was a brother to the human at an earlier point of development.’ (James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, Of the Origins and Progress of Language, Edinburgh, 1773-92).’ Gillian Beer, Introduction, Charles Darwin Origin of Species 1859, Oxford University Press, 1998

‘But there is more to comparative gemonics than just providing clues to genetic influences on diseases. It also lets us ask fundamental questions about human and animal minds.’ Monise Durrani, BBC Science

‘Chimpanzees are so closely related to humans that they should properly be considered as members of the human family, according to new genetic research. Scientists from the Wayne State University, School of Medicine, Detroit, US, examined key genes in humans and several ape species and found our "life code" to be 99.4% the same as chimps. They propose moving common chimps and another very closely related ape, bonobos, into the genus, Homo, the taxonomic grouping researchers use to classify people in the animal kingdom. Humans, or Homo sapiens to give the species its scientific name, are the only living organism in the genus at the moment - although some extinct creatures such as Neanderthals (Homo Neanderthalis) also occupy the same grouping. "Since people have been studying primate evolution, there's been this dichotomy between humans and the apes," said Dr Derek Wildman…"And so what we've shown is that humans and chimpanzees are actually more similar to each other than either is to any of the other apes," he told BBC News Online. Modern genetic science offers researchers another way to establish the relationships between different species, by measuring the similarity of their DNA code. It is a far cry from the traditional way of categorising organisms on the basis of what they look like, either live or in fossil form. The Detroit team compared 97 important genes from six different species: humans, chimpanzees, gorillas, orang-utans, Old World monkeys, and mice. From this, the scientists constructed an evolutionary tree that measured the degree of relatedness among the organisms. According to this analysis, chimpanzees and humans occupy sister branches on a family tree, with 99.4% genetic similarity. Next on the tree are gorillas, then orang-utans, followed by Old World monkeys. None of the primates were closely related to mice, which were used as a control. Dr Wildman said: "You could say that humans and chimps are as similar to one another as say horses and donkeys. "And there really isn't much evidence for them to be divergent at the family level, which would be something like the divergence between apes and monkeys…here's been as much change on the lineage on the line leading to chimpanzees as there has been on the lineage to humans since they last shared a common ancestor around six million years ago." The Detroit team says its work supports the idea that all living apes should occupy the higher taxonomic grouping Hominidae, and that three species be established under the Homo genus. One would be Homo (Homo) sapiens, or humans; the second would be Homo (Pan) troglodytes, or common chimpanzees, and the third would be Homo (Pan) paniscus, or bonobos. Not all scientists will accept the new classification. Whereas Dr Wildman's team find that chimps and humans are 99.4% similar, other researchers last year put the similarity at around 95%; the figure you get depends on precisely which genetic differences you look at. As to whether this will improve the lot of chimpanzees themselves, a spokeswoman for the conservation group the Jane Goodall Foundation was sceptical. The problems of habitat loss and commercial bushmeat hunting would continue whatever genus we put them in, she said.’ Richard Black, BBC Science Correspondent, BBC News, 2003

“Actually I’m not so sure we’d like to be classed as ‘human’ - if I might express my opinion through the medium of imagination, given that we have not developed the FOXP2 gene as expertly – or noisily – as yourselves, (but smell much better). From what we’ve seen of humans – murderous, destructive, selfish, exploitative, disease-ridden, I think we’d rather stay classified as we are, thanks.” ‘Charles’, Chimpanzee, 2006

‘We frisked about on many a tree/ For ages ere we changed our shape,/ And left the genial Chimpanzee/ To take our place as premier ape.’ The Angler on His Ancestry, Thomas Thornely, 1855-1949

Chimpanzee Genus Classification

Six million years ago - we left our recognisable selves

in the trees; who has not felt the whoosh of that luxury

hair, swinging from a branch, pole; wanted to reach back

when rheumy chimpanzees at the zoo hold out their hands

beseechingly - what we would call, humanly - seeing our

hand printed in this leathery precursor. Who has not seen

in chimpanzee eyes the truth about origin, communality -

written as a brown sign, veneered with tears. Who cannot

see the Genome’s power and artistry, slight shift; variations

making plastic molecules dance to wildly different tunes, or

this note by note piece, alike in all respects; hearing the same

music with the same ear - being the same silver strings played

by the same hand, just tuned slightly to become Pan troglodytes;

and is he not maybe more more deserving to be classified Homo

Sapiens than those given this massive advantage; high noble title.

*

Will we recognise them at last, our wild brothers;

hunted, exploited, captured - even while looking

at us, telling us this was wrong, so obviously;

something by way of belated shame, apology.

If they could just have spoken - why did this gift

come to us, like Promethus’s fire from heaven -

why were we given Earth if we would destroy -

was it beyond belief we would have squandered

beauty, killed our brother who even looks like us -

has our hands, our eyes, our feet. How they cradle

their babies - they are clearly mothers, yet murdered,

their children stolen, orphaned, kept as doll, trinket -

would they have rights if we gave them promotion -

raised their status, grouped them with us? Or should

the new classifaction of every creature be - as the Genome

tells her story, surrenders her legends, all Earth’s Children.

‘Humans and chimpanzees are more closely related than we thought. Scientists made the reassessment after studying 53 stretches of DNA scattered throughout the human genome, and comparing them with similar stretches in the genetic codes of a chimp, a gorilla and an rang-utan. The research also suggests that the human line diverged from the chimp evolutionary line between 4.6 and 6.2 million years ago. The research was carried out by Feng-Chi Chen of the National Tsing Hua University in Taiwan and Professor Wen-Hsiung Li of the University of Chicago, US. The team looked at DNA from an Asian male that was not associated with active genes. After finding the equivalent sequences in other primates, the scientists looked for differences in the two codes. The researchers discovered that human and chimp DNA differs by just 1.24%, half a per cent less than had been thought. Humans differ from gorillas by 1.62% and from orang-utans by 1.63%, again less than had been believed. The genetic differences studied by the researchers arise through mutation - they are errors that creep into the code as it is copied. Because these errors occur, on average, at a steady rate, they can be used to "look back" in genetic history and provide an estimate of how long ago the primates diverged into separate species. Orang-utans were the first to separate, between 12 and 16 million years ago; gorillas between 6.2 and 8.4 million years ago and finally humans and chimps went their different ways between 4.6 and 6.2 million years ago.’ Dr David Whitehouse, Science Editor, BBC News Online, 2001

‘A first draft of the chimpanzee genome sequence has been completed, US researchers announced. Investigators, funded by the National Human Genome Research Institute (NHGRI), also aligned the chimp sequence with the human sequence to facilitate comparisons. All data from the draft sequence, which covered most of the chimp's 3.1 billion bases, has been made publicly available. Scientists in the United States, Europe, and Japan will now begin analyzing that data and comparing it to the human sequence in hopes of finding clues to genome evolution, disease genes, and regulation…The chimp genome's similarity to the human's, however, may make it a less useful tool for disease gene finding than the genome of a more distant relative. "Every gene has its best model organism," Wilson said. "For some disease genes, the chimp's going to tell you a lot. For others it won't tell you much because it's too close to the human.’ GenomeBiology.com, 2003

‘The genome of our closest living relative – the chimpanzee – has been released by an international consortium of scientists.The chimp genome sequence, which consists of 2.8 billion pairs of DNA letters, will not only tell us much about chimps but a comparison with the human genome will also teach us a great deal about ourselves. “The major accomplishment is that we now have a catalogue of the genetic differences between humans and chimps,” says lead author, Tarjei Mikkelsen of the Broad Institute in Cambridge, Massachusetts, US. In keeping with previous studies comparing much smaller portions of the chimp and human genomes, the new comparison shows incredible similarity between the genomes. The average number of protein-changing mutations per gene is just two, and 29% of human genes are absolutely identical. What is more, only a handful of genes present in humans are absent or partially deleted in chimps. But the degree of genome similarity alone is far from the whole story. For example, the mouse species Mus musculus and Mus spretus have genomes that differ from each other to a similar degree and yet they appear far more similar than chimps and humans. Domestic dogs, however, vary wildly in appearance as a result of selective breeding and yet their genome sequences are 99.85% similar. So most of the differences between chimp and human genomes will turn out to be neither beneficial nor detrimental, in evolutionary terms.The real challenge then will be finding the changes that played a major role in the evolution of chimps and humans since the two lineages split, 5 to 8 million years ago. Nothing obvious has leapt out of the initial analysis. “From this study, there’s no silver bullet of what makes chimps chimps and humans humans,” says Evan Eichler of the University of Washington at Seattle, US. Comparing the two genomes has thrown up numerous candidates for what makes humans different though. One such set came by comparing 13,454 specific genes in the chimp and human genomes, looking for signs of rapid evolution. For each gene, the researchers compared the number of single letter mutations that alter the encoded protein versus silent mutations that have no effect. Silent mutations are possible because most amino acids are coded by more than one 3 letter DNA ‘word’ - for example, proline is coded by CCU, CCC, CCA, and CCG, so a change at the third position makes no difference to the protein.Comparing the two types of mutations allowed the team to spot genes that have had changes favoured by natural selection while taking into account the background mutation rate. And 585 of the genes studied in this set – many involved in immunity to infections and reproduction – had more protein-altering mutations than silent ones… But comparing genome sequences can only tell scientists so much. Now begins the methodical job of homing in on the promising parts of the sequence and identifying the differences that count. “This is best viewed as an exciting starting point,” says Simon Fisher at the Wellcome Trust Centre for Human Genetics at Oxford University. “In the same way that knowledge of our own genome sequence has not automatically led to a full understanding of human biology, so the decoding of other primate genomes will not, by itself, reveal exactly what sets us apart.” New Scientist, 2005

‘Humans evolved to walk upright because it uses less energy than travelling on all fours, according to researchers. A US team compared the energy used by humans and by chimpanzees in walking. The human bipedal gait is about four times more efficient than chimps getting around on either two or four legs, the researchers found. Writing in Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS), they say this may explain why we walk bipedally, and some of our anatomical features. Other research groups have proposed alternative explanations for our two-legged gait. Some suggest it evolved because early humans needed to reach upwards to collect food or pass it to a mate, while others maintain it predates four-legged locomotion in primates, citing the often upright posture of orangutans as they move across slim branches…The hypothesis, then, is that early humans began to evolve in a direction which allowed for easy bipedal travel. David Raichlen suggests that early humans should show adaptations such as a longer leg length, and that there are indications of this in fossils of the genus Australopithecus, such as the famous "Lucy" specimen discovered in Ethiopia in 1974.’ BBC, 2007

They stayed in the garden eating fruit

They stayed in the garden eating fruit,

swinging among leaves - but happier

they look than us - who walk upright,

look full at the sky, such inspirational

colour - but are always guddling in the mire,

mucking ourselves up, having to symbolically

wash; remind ourselves of what is right, true -

rather than just being as they are – so content.

The Human Genome’s curse and gift – chains

of DNA that will not let us be at peace; what

force has driven us thus to covet, envy, mutate

the need to cherish - forget all else so much of

the time but the grasping future, ankle-grabbing

past; when this sunlit moment, this humble urban

street flower illuminated as today’s Flower of Flowers;

sun-cup - harbourer of hot yellow light fallen straight

from the Sun’s burning heart to just here – right there

in this spun vessel of cholorophyll and photosynthesis,

demonstrating possibilities of all this bright chemistry

around – there is enough happiness in a single flower

to fuel the human heart for a full day and night; before

forgetting this simplicity, lack of complication - stuck

in our own web, struggling against prevailing streams,

passing life - turning burn in spate as we suddenly age.

The chimpanzee has developed peace in those eyes

by millennia of being in harmony among the leaves –

he will not raise a gun to us, no matter what murders,

though we have stolen his children for meat - to dress

in our clothes, as cannibals, usurpers, thieves, heathens

in the expansive church of nature; such sorrows he tells,

both hands curling around bars, dumb tongue out gently.

‘Scientists today came one step closer to a biological understanding of what makes us human with the deciphering of the genetic make-up of the chimpanzee. The ape is mankind's closest living relative. Differences between its DNA and that of humans could point to a genetic explanation how we developed such traits as walking upright and the use of complex languages. The work has produced a long list of DNA differences with chimpanzees and some hints about which ones might be crucial. "We've got the catalogue, now we just have to figure it out," said Dr Robert Waterston of the University of Washington School of Medicine in Seattle. "It's not going to be one gene. It's going to be an accumulation of changes." Dr Waterston, the senior author of one of several related papers appearing tomorrow in the journals Nature and Science, presents a draft of the newly deciphered sequence of the chimp genome, in which an international team of researchers identified virtually all the roughly 3bn building blocks of chimp DNA. "It's a huge deal," said Dr Francis Collins, the director of the National Human Genome Research Institute, which provided some support for the project. "We now have the instruction book of our closest relative." He said the work will help scientists analyse human DNA for roots of disease. Humans and chimps have evolved separately since splitting from a common ancestor about 6m years ago, and their DNA remains highly similar - between 96% and 99% identical, depending on how the comparison is made. The number of genetic differences between a human and a chimp are however 10 times more than between any two humans. Waterston and his colleagues looked, for example, for genes that apparently have changed more quickly in humans than in chimps or rodents, indicating they might have been particularly important in human evolution. They found evidence of rapid change in some genes that regulate the activity of other genes, telling them when and in what tissues to become active. With the help of chimp DNA, his team also discovered beneficial genetic changes that spread rapidly among humans. One area contains a gene called FOXP2, which previous work has suggested is involved in acquiring speech. The papers were published as conservationists unveiled a £17m plan to save the great apes of Africa, which are under threat of extinction from disease and human activity. Russell Mittermeier, the president of Conservation International, said poaching for the bushmeat trade, rampant logging and the Ebola virus are putting the western lowland gorilla and the central African chimpanzee on the cusp of extinction. While experts say precise estimates for remaining ape numbers are difficult to pin down, there is a consensus among conservationists that they are in steep decline. The plan designates 12 sites in five countries - Cameroon, Gabon, Congo, Central African Republic, and Equatorial Guinea - where emergency programmes will attempt to protect the apes. Waterston and his co-authors said they hoped documenting the overall similarity of chimp and human genomes will encourage action to save chimps and other great apes in the wild. "We hope that elaborating how few differences separate our species will broaden recognition of our duty to these extraordinary primates that stand as our siblings in the family of life," he said.’ Guardian newspaper, UK, 2005

‘The researchers discovered that a few classes of genes are changing unusually quickly in both humans and chimpanzees compared with other mammals. These classes include genes involved in perception of sound, transmission of nerve signals, production of sperm and cellular transport of electrically charged molecules called ions. Researchers suspect the rapid evolution of these genes may have contributed to the special characteristics of primates, but further studies are needed to explore the possibilities. More than 50 genes present in the human genome are missing or partially deleted from the chimp genome. The corresponding number of gene deletions in the human genome is not yet precisely known. For genes with known functions, potential implications of these changes can already be discerned. For example, the researchers found that three key genes involved in inflammation appear to be deleted in the chimp genome, possibly explaining some of the known differences between chimps and humans in respect to immune and inflammatory response. On the other hand, humans appear to have lost the function of the caspase-12 gene, which produces an enzyme that may help protect other animals against Alzheimer's disease.’ Genome.gov, 2005

Cultivating FOXP2

Genetic surge, spirit still rippling over the waters;

expanding energy sparking dull molecules - step

change in the dance hardly noticed, but growing -

accumulating difference, manipulating the means

for the word of the human, sound from his mouth -

working his tongue to the declarative scales of love,

pity, comfort; voice singing out of starless darkness.

‘There are four subspecies of chimpanzee, all are classified as Endangered by the IUCN. Once common in the African forest belt that stretched from Senegal in the West to Tanzania in the East, there are now fewer than 300,000 left and their numbers are declining across most of their range. The forest home of the now famous Gombe chimpanzee's in Tanzania has become an island as neighbouring villages gradually chop into the forest edges for firewood and agricultural space. Bonobos are found only in the DRC south of the Congo River, and are also Endangered. The bonobo population has decreased dramatically in recent years.’ BBC, 2006

‘The genetic blueprint of the chimpanzee, humanity’s closest cousin, has been mapped in its entirety by scientists, narrowing the search for the genes that make us human. Comparison of the chimp genome with its human equivalent has already revealed small but striking differences that could explain distinctly human traits such as language, and further analysis promises critical insights into the health and evolution of our species. The two most sophisticated great apes share almost 99 per cent of their functional genes, and even when differences in less significant DNA are taken into account they remain 96 per cent identical. Of the three billion genetic letters or “base pairs” in which both genomes are written, just 40 million - fewer than 4 per cent - are not perfectly identical in humans and chimps. Robert Waterston, of the University of Washington in Seattle, one of the leaders of the international research team, said: “Within those 40 million differences are clearly the genetic bases of what makes us human. As our closest living evolutionary relatives, chimpanzees are especially suited to teach us about ourselves. We still do not have in our hands the answer to a most fundamental question: what makes us human? But this genomic comparison dramatically narrows the search for the key biological differences between the species.” …About 53 human genes that are completely or partially absent in chimpanzees have so far been identified, including several that seem to affect medical characteristics such as susceptibility to Alzheimer’s disease and diabetes. There appear to be too few of these major genetic changes, however, to explain the differences between humans and chimps, such as brain size and sophistication, language and an upright, bipedal gait. Early comparisons of the two genomes suggest that many distinctions emerge instead from subtle changes in the way that similar genes are switched on and off in each species. The DNA used to map the chimpanzee genome, which is published today in the journal Nature, came from the blood of an adult male called Clint, who was kept in captivity at the Yerkes National Primate Research Centre in Atlanta, Georgia. Clint died last year of heart failure at the relatively young age for a chimp of 24, but two colonies of his cells have been preserved for future study. A first draft of the genome was published in December 2003, and the finished version is now also complete. The chimpanzee is only the fourth mammal to have its genome sequence completed, after humans, rats and mice, though a draft is available for the dog. Of these species, humans and chimps are by far the most similar. The differences between them are ten times fewer than those between mice and rats, and sixty times fewer than those between humans and mice. Any two humans, however, are ten times more similar genetically than any person is to a chimpanzee. The degree of genetic proximity between people and chimps has led scientists to call for tougher worldwide restrictions on their use in research. Vivisection on any of the great apes is already banned in Britain.’ The Times newspaper, UK, 2005

That blue pulls me

That blue pulls me. But a great burning yellow flower

hurts my eyes - under the green shade I shelter the day,

while fruit swells for me, plumps for my belly, the hand

I keep watching - manipulating the branch, food, leaves.

I screech out to the others, feeling something in the sound -

a longing, some harmony with the whooping birds perhaps;

something requiring concentration, distillation - something

more. Hot light slits through dripping banana leaf stencils -

slashes moist ground where my toes cool. Bananas are hands

like mine – I desire to gather, set a bunch here in the sunlight

to see how much more yellow, dazzling, their fingers become.

The bones of my hips creak, but I am the tallest, stretching up.

‘He gave an impression of dignity and restrained power, of absolute certainty in his majestic appearance. I felt a desire to communicate with him… Never before had I had this feeling on meeting an animal. As we watched each other across the valley, I wondered if he recognized the kinship that bound us.’ The Year of the Gorilla, George Schaller, University of Chicago Press, 1964

‘After many years of language training/ in the Yerkes Primate Lab (our animals/ have indoor/ outdoor access and may/ withdraw from lessons at will) Sherman/ the chimp, after correctly categorizing// socket wrench/ stick/ banana/ bread/ key/ money/ orange// as either food or tool, used the incorrect lexigram to classify a sponge…/ Sherman’s apparent mistake/ was subsequently read/ as the interpreter’s/ misunderstanding of the animal’s/ intent. An active eater,/ Sherman is prone to/ sucking liquids from a sponge,/ often chewing and swallowing/ the tool as if it were food.’ Alison Hawthorne Deming, Essay on Intelligence: Three

A blaze in the brain

A blaze in the brain - firing cells, welding, re-wiring

in the flames that came from the original sky; space.

There were stars in those molecules, new gases, germs -

what sounds would come from that bright celestial noise,

what pattern come calling to develop the hand, shining eye;

crying out for realisation, expression, new ways to make, be.

What stirring of molecules by what hand – some sublime energy

without limitation, but tuned to goodness, creative use, denial of

everything wicked - combating this because doing the right thing

is a light, guidance, hard-wired; overridden to produce corruption,

negativity, bad deeds that rankle - or the spiritual chill of no guilt.

What rubbing of molecules kindled the sparkling shifts, Christmas

tree brain, sudden Blackpool Illuminations; the teetering, lengthening

of white bone, wingless arms stretched out on the tightrope of ground,

earth beneath the feet - getting back down to the floor of the garden -

and the stone picked up, weighed in the fingered hand, contemplating

its dull shine; its shape like a leaf; knowing the unknown entirety

of stone still not fossiled in the mind - wondering at its existence,

being there with you in the forest - that first compulsion -

faint, inactive, seed of manipulation; what was his name,

or their names that felt the primary shiver to operate this stone -

stick; crush the hull, scrape husk, cultivate dreams of cathedrals.

‘Lying on his side, tied by his waist to the top of a tiny wire cage, the infant was damp with sweat, his eyes glazed. He looked close to death. Yet when I made the tiny panting sound of a chimpanzee greeting, he sat up and reached to touch my face. What a dilemma: buying such a sad little orphan may encourage the capture and sale of live animals. Almost certainly the infant was a by-product of the bush-meat trade, the commercial sale of meat from animals shot in the forests; there's so little flesh on an infant chimp that the hunter will often try to sell the infant as a pet. But hunters will also shoot a mother deliberately in order to steal and sell her infant.’ Jane Goodall and Michael Nichols, BBC Wildlife magazine, 1999

‘The Bornean orang-utan is listed as Endangered by the IUCN. The Sumatran orang-utan is the more threatened of the two species, listed as Critical rather than Endangered, by the IUCN. This means it is 'facing an extremely high risk of extinction in the wild in the immediate future'. Seven subspecies of gibbon are registered as Critically Endangered. Besides habitat loss, they are also threatened by the illegal wildlife trade (often body parts are sold for use in traditional medicines) and by poaching. One of the gibbon species most at risk is the moloch or Javan gibbon. It feeds on ripe fruits in the upper canopy of the rainforests in Java. Fewer than 2,000 Javan gibbons survive in the wild. Java is one of the most densely populated islands in the world, so its natural rainforest habitat is disappearing rapidly due to logging and agricultural demands.’ BBC, 2006

Walking in each other’s footsteps, genetically

hand in hand - the Genome’s lucky cultivation

of particular genes brought us to speech, music

beyond water in leaves - exotic birds, monkey

sounds; left them happy among trees and fruit,

in verdant communion of Chimpanzee society,

home; production of rain and oxygen overhead,

forest bustle, hairy babies even more like theirs -

the Bad Ones, us - the big bald hunters, murderers.

How we must seem to these fated creatures, gently

eating fruit, being magnificent; jigsawed obviously

by Evolution, though even these strong visual clues,

heart-knowledge, science, is not enough to stop it –

‘Critical, Endangered, Red List, Nearing Extinction -

Extinct’ - these are the new black classifications hand

in hand with this new knowledge of our close kinship;

genetic detail to match the eyes - Bornean Orang-utan,

Sumatran Orang-utan – all species and sub species are

Threatened – as Ape Brethren, Naturekin, Haired Map

of Mankind; of magnificent Primates, Gibbons, the Ten

Primates Most in Danger of Imminent Extinction, are -

Miss Waldron’s Red Colobus - possibly extinct in Cote

D’Ivoire, Ghana - Diademed Sifaka from Madagascar;

Mentawai Macaque, Indonesia, Sclater’s Black Lemur,

Madagascar; the Roloway Guenon, also Cote D'Ivoire,

Ghana; Brazilian Bare-faced Tamarin native to Brazil -

Golden Crowned Sifaka of Madagascar; White Collared

Mangabey, Cote D'Ivoire; Stampfli's Greater Spot-nosed

Guenon, Cote D'Ivoire, Liberia - Golden Bamboo Lemur,

also Madagascar - each name spells a word in the Primate

Poem; each name the living mark of the Genome’s ancient,

creative poem, matching man and mouse, but man and ape

so obviously, each Primate here a magnificent month in our

breathing calendar of Evolution’s wild creativity – so slowly

explosive; so orderly from the core among water, light, stars.

What must they do – this Nature, these Creatures, God or Man,

to qualify for our protection, when even beauty is over-thrown -

not just fairy-armoured beetles no longer creeping among grasses,

small brown clattering of the earwig never knowing his Scots name,

‘Horny Golloch’ - those rustling co-ordinates of organic light, now

sparse, whispering - still unnamed, falling silent; tears of unhinged

flowers, falling unnoticed among these dying perfumes of the day -

but the embering tiger that wrote fire from mud, space and water;

Birds of Paradise that remember Heaven in the physical feather –

the long chapter of apes that wrote our particular hands, feet, eyes;

our fur-brothers - our animal kin - wearing clues upon their bodies

to the shared verse; a spiny pufferfish hard to understand, embrace,

but the communal movement in the composition of the ape and us -

such close harmony can be heard as startling as noises in the jungle,

the whooping bird, snarl and howl as we wander, leaving our sterile

message now, our burning feet, our ploughshare as sword, machete;

our slashing of poetry undisturbed in the story of the trees laid down

and writing endlessly, still dripping with new words and possibilities.

Our path, the Genome’s sparkling path, was strewn with flowers,

with birds, insects, such fantastic animals – behind us is concrete,

still bursting through with shoots and claws, horns, wings and fur,

but growing as a grey skin; a terrible monument to apes and Earth.

Info, IUCN ‘Red List’, 2006

‘The diademed sifaka is one of the largest living lemurs, and lives in groups of between two and five animals in the eastern rainforests of Madagascar. They have not been extensively studied in the wild and have never reproduced in captivity, so little is known about their natural history and ecology. They are threatened by habitat loss and are hunted for food throughout much of their range. Six hotspots are judged the highest priorities for the survival of the most endangered primates. They are Indo-Burma, Madagascar, Sundaland (the islands of Sumatra, Java and Borneo), the Guinean forests of West Africa, the Atlantic forests of Brazil, and the western Ghats/Sri Lanka and Himalaya. Primates all over the world suffer from habitat loss, the bushmeat trade, human-wildlife conflict, the research or pet trades and disease.’ BBC, 2006

‘Despite similarities in the overall sequence, the human and chimpanzee chromosomes compared have some structural differences, including one large section that is flipped backwards in humans compared to chimps. Such an inversion makes it impossible for the two chromosomes to pair up when the cell divides to create sperm and eggs. Over time, that incompatibility could have driven a reproductive wedge between the evolving populations.’ Wellcome Trust, 2004

‘The International Human Genome Sequencing Consortium (IHGSC) recently completed a sequence of the human genome. As part of this project, we have focused on chromosome 8. Although some chromosomes exhibit extreme characteristics in terms of length, gene content, repeat content and fraction segmentally duplicated, chromosome 8 is distinctly typical in character, being very close to the genome median in each of these aspects. This work describes a finished sequence and gene catalogue for the chromosome, which represents just over 5% of the euchromatic human genome. A unique feature of the chromosome is a vast region of 15 megabases on distal 8p that appears to have a strikingly high mutation rate, which has accelerated in the hominids relative to other sequenced mammals. This fast-evolving region contains a number of genes related to innate immunity and the nervous system, including loci that appear to be under positive selection - these include the major defensin (DEF) gene cluster and MCPH1, a gene that may have contributed to the evolution of expanded brain size in the great apes. The data from chromosome 8 should allow a better understanding of both normal and disease biology and genome evolution.’ Nature, 2006

‘In April 2001, the first genetically modified primate was born. Andi the monkey was made from an egg that had been modified to include a simple jellyfish gene. This breakthrough proved that it is possible to genetically engineer primates. Andi is the closest relative of a human to be genetically engineered.’ BBC Science Online

“Do Andi’s legs ever turn to jelly?” Gillian K Ferguson

COMMON PLACENTAL MAMMAL ANCESTOR

‘Researchers have re-created part of the genome of the common ancestor of all placental mammals, a small shrew-like creature that prowled the forests of what is now Asia more than 80 million years ago. By comparing DNA sequences of 19 species of existing mammals, including humans, the researchers have reconstructed a large segment of DNA in the species from which all of today's placental mammals arose. They estimate that the reconstruction is 98 percent accurate. The project, led by David Haussler, a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator at the University of California, Santa Cruz, based their reconstruction efforts around a region of the genome that covers about 1.1 million bases flanking the cystic fibrosis transmembrane conductance regulator (CFTR) gene. That region of the genome has been sequenced in a large number of species. Efforts to extract DNA from fossils generally have been disappointing because DNA molecules break down over time. Geneticists therefore have turned to a technique that has been called '[computerised] paleogenomics' to infer the DNA sequences of past organisms. All of the placental mammals living today are descended from an early species that lived tens of millions of years before the final demise of the dinosaurs. This species underwent a rapid diversification, splitting into the evolutionary lineages that have led to today's placental mammals. Because all of these species are descended from a common ancestral species, they all have inherited specific DNA sequences from that ancestor. Reconstructing the DNA sequence of this ancestor is comparable to drawing conclusions about the first automobile by observing the many different kinds of automobiles existing today. Though the separate makes of automobile have changed and diversified over time, they share features that were present in their conceptual ancestor: four rubber tires, a windshield, and an internal combustion engine, for example. The challenge for Haussler and his colleagues was to determine how the DNA sequence of the common ancestor changed in each of the evolutionary lineages leading to current mammals. This task is not so complicated where individual nucleotides changed in a particular lineage, because the original nucleotide often was retained in other lineages. It is much more difficult where stretches of DNA were inserted or deleted in the genomes of particular species. "DNA comes and goes," said Haussler. "Some DNA gets deleted, and new DNA gets inserted. Tracking the history of these insertions and deletions is essential." Haussler's research team built a computer program that looked both for individual nucleotide changes and for insertions and deletions in the DNA sequences of a number of mammalian species, including species of pig, horse, cat, dog, bat, mouse, rabbit, gorilla, chimpanzee and human. Knowing about the genome of the common ancestor of placental mammals creates tremendous scientific opportunities, according to Haussler. Most important, it reveals how DNA sequences have changed in each of the lineages leading to one of today's mammalian species. For example, studies of the FOXP2 region of the genome indicate that changes in FOXP2 may have contributed to the evolution of fluent speech in the human lineage. "The nucleotide is C for more than 300 million years, and then suddenly it's A, just in the human lineage," said Haussler. "You can see it. That's the excitement of documenting these dramatic events that can change the nature of an organism over evolutionary time.’ Haussler said he is confident that significant medical benefits will accrue from a better understanding of the genome, although this particular project was motivated by pure scientific curiosity. "I want to know in molecular detail how we evolved from a furry, nocturnal, shrew-like creature, and now is the time to find out”.’ Wellcome Trust, 2004

My mammalian extended family

My mammalian extended family remembers

burrowing under rusted leaves in cool night;

snores of stomping dinosaurs now sleeping,

scuttling over dragon feet - sniffing nosily

into forest nooks and crannies - insect lights

burning over supper, evolving incandescence.

Looking down I recognise my old pink hands -

my almost whiskers twitching, still alerting me

to anything untoward in the 21st century. Still,

I recollect this sense of smell - when no scent

registers, unless the forceful flower sugars -

their intoxicating liquors held out on tongues

for men or bees, their seductive gold dustings,

means of honey. My mammal memories are

fresh to the immortal genes, still furred, cosy;

there are bats and moons - the smell of earth,

wet and sumptuous as a mouth – I will freeze,

stutter, startled, though now I clutch my heart

that grew from the red breast of a rose - a robin.

And these genes will not read the word of death

until the end of all life on the adapting, skilful planet,

not while one caterpillar and one green leaf remains –

after the unnecessary cessation of all breathing creatures,

begun by these placental mammals susceptible to ozone

depletion, toxins, pollution; vulnerable to lack of water -

that little shrew we were never dreamt - among his root

music, poems he read written in stars across the sky,

trees scribbling spindly verses upon the paper Moon,

the far-off song of a flower hungry for children,

and the moths, sick with lust, lumbering there –

of our trouble; his nocturnal eyes in such daylight

as burns the retina, bald body, infiltrates our DNA,

not with messages of Mozart, Einstein to come,

the artist or surgeon in his paws; but a requiem.

‘Our own shrew-ancestor/ was a Nobody, but could still take himself for granted, with a poise or grandees will never acquire.’ WH Auden, 1907-1973, Unpredictable but Providential

Mammal Grown from Water

I was alive then – imagine, as dinosaurs stomped,

breathing that giant-fern air, dragonflies the size

of eagles - immense breath of steamy Evolution.

I was warm by then – I recognise the heat of blood -

this red, magicked from circulating molecules of sea,

hot effort of dragging stumpy web-legs from reluctant

water on budding, muscular fins, bent as fallen wings -

to my imagining of blue, this lightness, easy movement;

tuning my eyes, adapting cells by unknown compulsion.

Among jungle, my memory flexes; in wet shadows,

slips back to smallness, rustling, a twitchy alertness

like the modern scent of a burglar, his strange sound.

My hands in earth play the crumbled texture

like an instrument - music comes from pink

fingertips; tuning soil, listening for worms,

footsteps, residual touch of early light printed -

faintly luminescent even now in dripping night,

two little stars of my eyes in immense darkness.

As dawn comes, I patter to rest, fantastic creatures

stretching for the next shift of life - every moment

must be filled for this continuous poem to go on -

writing, fulfilling the script. Already, I am fur

grown from water, scales; my nose is sensitive

to fluctuations of air, passing of wings, giants -

I do not think of my own insignificance; being

alive is the thing, my shrew children existing -

my dreams are sophisticated in their simplicity,

as the codes of being I embody seem inadequate -

yet have made such kingdoms, too many miracles

to be seen still as holy by those familiar with life.

My warm brood will inherit the Earth – tonight,

under the huge yellow Moon touching my nose,

I smell the future, cosy in my skin, content; I am.

‘Conserved Non-Genic Sequences: an unexpected Feature of Mammalian Genomes - Mammalian genomes contain highly conserved sequences that are not functionally transcribed. These sequences are single copy and comprise approximately 1–2% of the human genome. Evolutionary analysis strongly supports their functional conservation, although their potentially diverse, functional attributes remain unknown. It is likely that genomic variation in conserved non-genic sequences is associated with phenotypic variability and human disorders. So how might their function and contribution to human disorders be examined?’ Nature, 2005

Wee Shrew-like Creature

Today, I feel like the wee shrew-like creature I was once -

80 million years ago. My burrow, soft cushions on the sofa,

nibbling sweet stores, my tail wrapped comfortingly around.

My eyes are big, black, smudgy, with lack of sleep’s natural

mascara - my sniffly nose elongates, oversensitive, so tender.

I wonder how I will face the lions strutting, proud, confident,

when I am a wee squeaky shrew-like creature, 80 million years

old. As night comes, opening my black eyes further - all pupil -

twin-starred, melancholy, my little mouse hands curled together,

I jump and twitch at the slightest sound, my whiskers quivering

as I feel the invention of tears begin in my big bald human body.

Why did I leave the forest, wrap of darkness, being insignificant.

MAMMALIAN GENOMES NEXT IN LINE FOR SEQUENCING - from New Scientist Print Edition, June 2005

‘What do pangolins, sloths and gibbons have in common? They are all in line to have their genomes sequenced. Last week the National Human Genome Research Institute in Bethesda, Maryland, announced a diverse list of target species that includes nine mammals: the pangolin, 13-lined ground squirrel, megabat, microbat, tree shrew, hyrax, sloth, bushbaby and northern white-cheeked gibbon.The idea is that by comparing the human genome to mammals that evolved from the same distant ancestor, we can identify shared or conserved DNA sequences. Conserved sequences have survived in different species because they have an important function - at least that's the theory (New Scientist, 5 June 2004, p 18). For the purpose of comparison, only rough, low-quality drafts of the genomes are needed.’ New Scientist, 2005

What a jolly mammal party!

What a jolly mammal party! - I like the sound of the ‘Megabat’

in particular; is he the size of an Eagle? And what’s a ‘Pangolin’?

Cross between a Panda and Penguin? And the Lesser Hedgehog -

does he have blunt spines? I’ve always had a soft spot for mossy

Sloths; Bushbabies, Shrews - though I wasn’t aware they could live

in trees. And Wallabies always sound fun, like Duck-billed Platypi.

‘Marmoset’ sounds like an orange Victorian condiment; comforting,

warm, slightly spiced. But even if they only inhabit our imagination -

until now as their word is recorded in the Book of the World, written

to disk, flesh poem transcribed; even if I never set eyes once in my life

on the Hyrax or Opossum - if David Attenborough never once whispers

with just-contained, shining excitement beside Sorex Araneus, European

Common Shew, going about his supper - each and every one is a matter

of great significance to me - their being, doing on the planet. Each one is

a particular poem written in the universal book, being read, reading aloud

in the cluttered world where the sound of poems is the transcription of life,

and the sound of their silence is not quite heard until late in the disaster of

a day, a world - this time - our time. Music altered, spoiled, desecrated; just

this one small note of the scared Tree Shrew confused by the loss of trees –

his suffering, starvation, disorientation, the simple story of one small shrew,

matters in ways we do not yet understand - even as we study Earth’s writing.

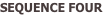

‘What are the comparative genome sizes of humans and other organisms being studied?

*Information extracted from genome publication papers below.